Choosing a Finish

Before you start your next furniture project, consider a finish's durability, its appearance, and its method of application.

There is such a bewildering array of finishes available that it can be difficult to choose the right one for any particular project. Some finishes are attractive and easy to apply but perhaps don’t offer the level of protection that a particular project warrants. Another finish might offer the durability you’re looking for but may add an undesirable color. In some cases, you may not own the proper equipment needed for application.

In this article, I’ll try to help you sort out these variables to arrive at a good choice. In the process, I’ll delve into the composition of the basic types of finishes and how you can amend them to suit your application purposes.

Factors to Consider

When it comes to choosing a finish, there are three primary considerations to take into account: durability, appearance, and method of application. Secondary considerations may include reparability, ease of rubbing out, or nontoxicity.

The first step is to determine how the piece will be used. Will it be subjected to a lot of moisture, solvents, or food? Is it likely to suffer abrasion and scrapes, or will it be primarily a display piece? This affects the level of durability you’ll need from a finish.

The next important decision is how you want the finish to look. Do you want the “in-the-wood” appearance that a thin finish provides, or do you want a thicker finish that accentuates depth? And do you want the finish to add color to the wood, such as a yellow tone? Or do you want to minimize the chances of the wood changing color as it ages?

Do you have the right equipment to apply your chosen finish? And do you have a finish area that is clean, heated, and dry for properly doing the work? Is it equipped so you can safely spray flammable solvents?

Determining the answers will help you target the best finish for the job. But before I discuss the appropriate finishes, it’s important to understand the two basic categories of finishes: evaporative and reactive.

Evaporative and Reactive Finishes

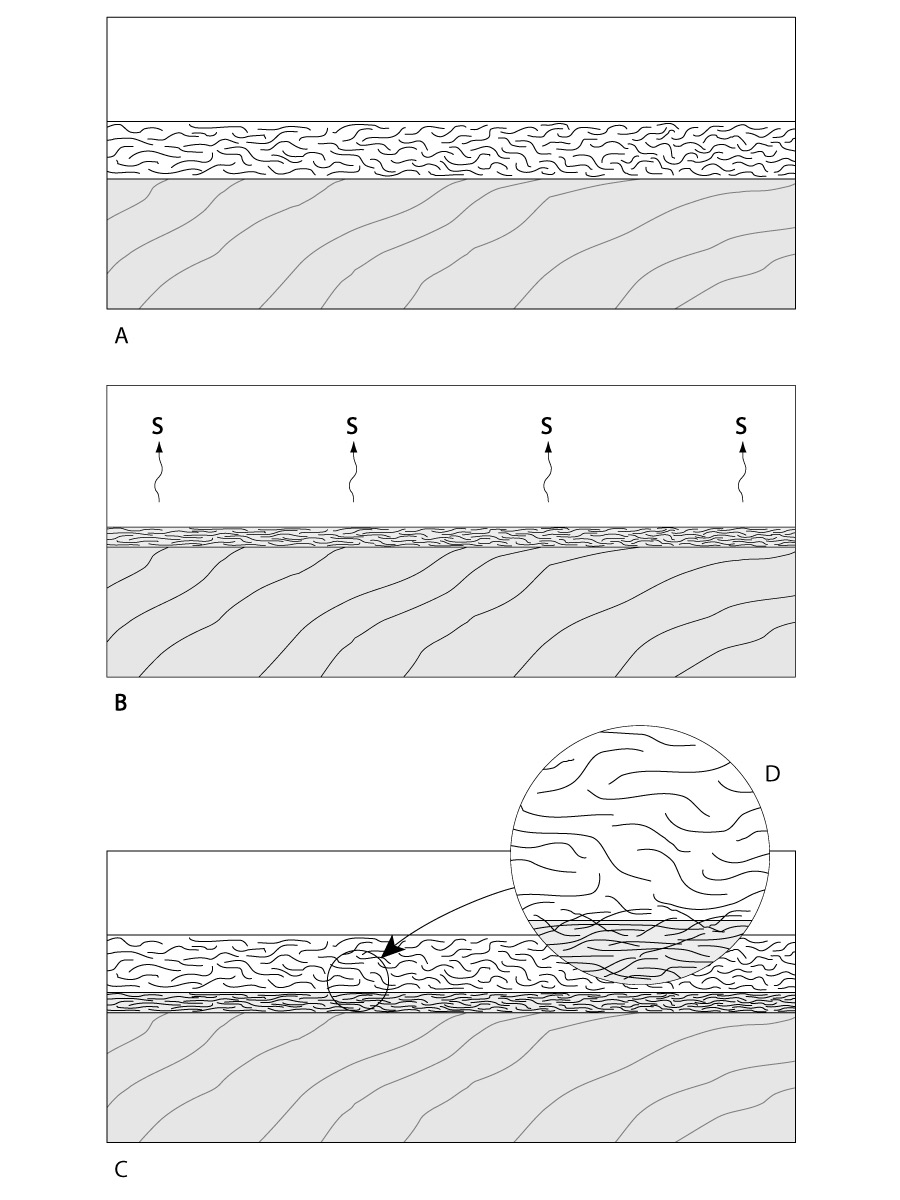

All finishes fall into one of two types: evaporative and reactive. These classifications are based on how the liquid resin cures into a solid, protective finish and can tell you a great deal about what to expect from a particular finish.

Evaporative finishes are made by dissolving the finish resin in solvent. These finishes cure by evaporation of the solvents in the finish. Common evaporative finishes include shellac and nitrocellulose lacquer. Because the resin does not undergo any chemical change, these evaporative finishes are referred to as “nonconversion” finishes. They are also called “thermoplastic” finishes because they are softened by heat.

Reactive finishes cure as a result of the resin converting into a different chemical compound. A reactive cure is known as cross-linking or conversion curing, because the liquid resin reacts with something else to form a new chemical compound. Two examples of reactive finishes are oil-based varnish and catalyzed lacquer. Varnish cures automatically by exposure to the oxygen in the air, while catalyzed lacquer only cures when you add a catalyst. Once the resin molecules convert into the hardened finish, they are no longer soluble in their original solvent, nor are they easily softened by heat.

Durability

The durability of a finish refers to its resistance to scratches, marring, heat, and damage from liquids. Durability is a prime consideration when you’re choosing a finish. If you’re looking for greater durability, a reactive finish is a better choice than an evaporative finish.

Evaporative finishes are less durable overall than reactive finishes because their resins can be softened or remelted by heat or certain solvents. This feature is good if you want to repair the finish later or rub it out, but the downside is that the finish scratches easily. Of the evaporative finishes, nitrocellulose lacquers and the acrylics fare the best for overall durability.

Except for the pure oils, reactive finishes are much more durable than evaporative finishes. Because the resin molecules are more tightly cross-linked, water cannot permeate the finish easily. They are also more solvent-resistant than evaporative finishes. Oil-based polyurethane is the most durable finish that you can apply by hand, while catalyzed lacquers, varnishes, urethanes, and polyester are the best for spray application. While there are exceptions, reactive finishes are generally harder to rub out and repair than evaporative ones.

Appearance

The three primary contributors to the appearance of a finish are its film-forming qualities, its color, and its depth of penetration into the wood. The main decision you’ll need to make is whether you want the kind of natural, “in-the-wood” finish look provided by a penetrating, non-film-forming finish, or the hard, clear, protective “lens” of a film-forming finish.

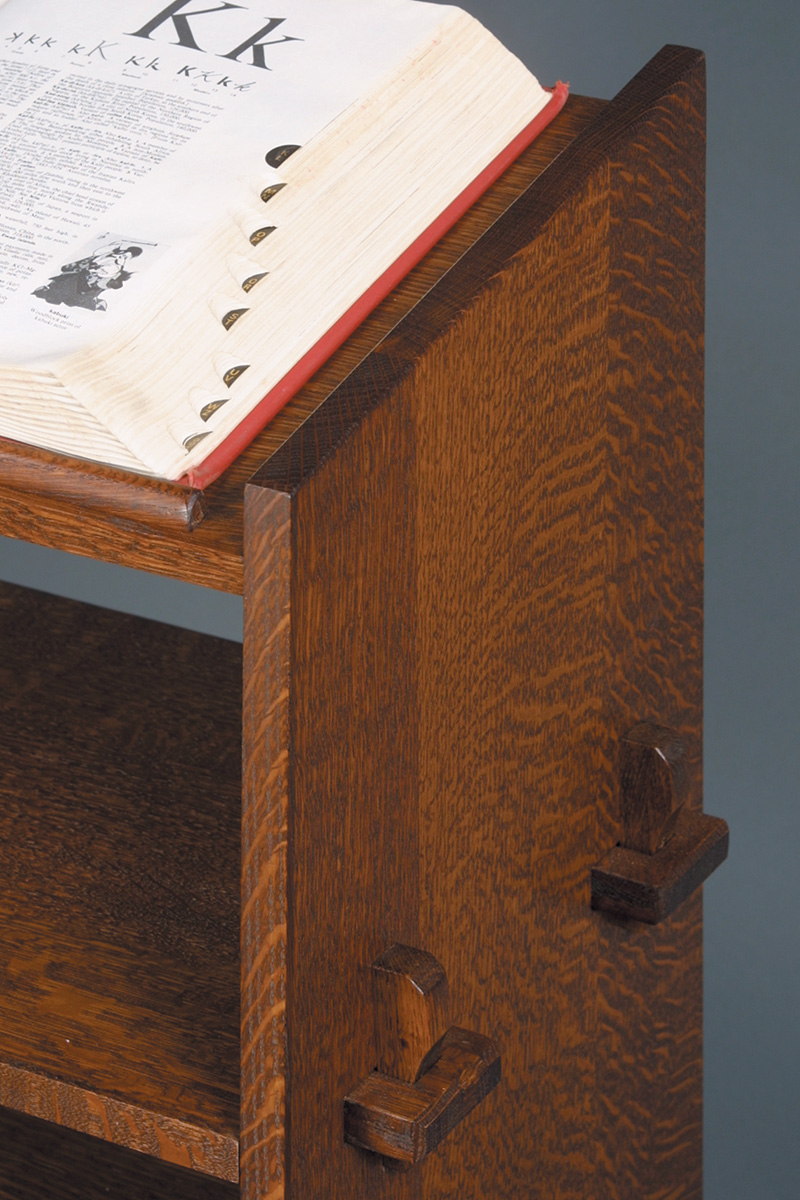

For a natural finish, woodworkers have long used true oils like tung oil and linseed oil, wax, or oil-varnish blends (like Watco). These nonglossy penetrating finishes harden within the wood, imparting a nice low luster to the surface. However, since they don’t form a hard, solid film on the surface, they offer limited protection against abrasion and liquids.

If you want durability and the deep, lustrous look of a filled-pore finish, you’ll need to use a hard, film-forming finish like shellac, lacquer, or varnish. These are the finishes used in conjunction with complex coloring options like toning and glazing. A point to consider is that as long as you don’t build up the finish beyond several coats, shellac, lacquer, varnishes, and catalyzed finishes can all be used for natural-looking finishes and will provide better protection than pure oil.

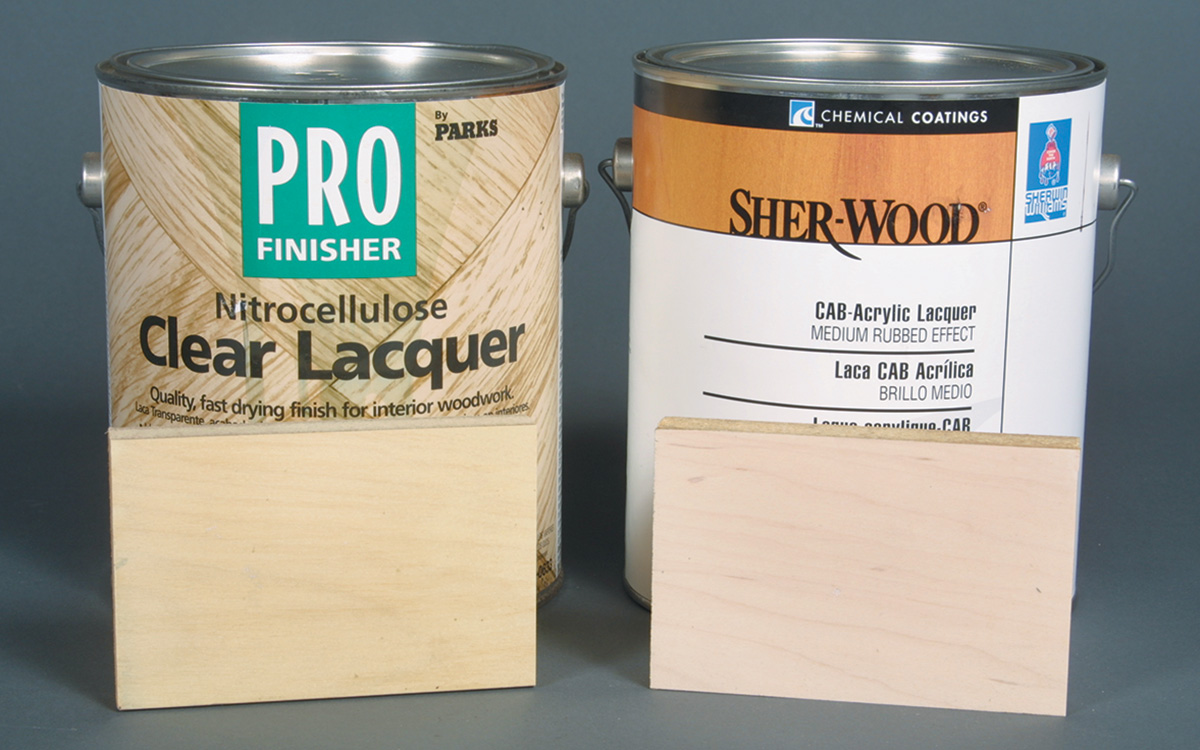

The color of a finish is also a consideration. Some finishes significantly deepen or darken the wood surface, increasing both depth and luster. Oils and oil-based varnishes do this the most, followed by solvent-based lacquers and shellac. On the other hand, most water-based polyurethane or acrylic finishes, as well as some catalyzed finishes, have a minimal effect on the natural color of the wood because they’re optically clear and tend to lay on the surface without penetrating deeply.

Dark finishes like orange shellac or tung oil/phenolic resin varnish may be too dark for woods you want to keep as light as possible. Some finishes can impart a yellow hue when applied over white-painted finishes.

Application Safety and Environmental Concerns

Solvent-based finishes like varnish and lacquer contain flammable and toxic solvents. Water-based finishes eliminate the danger of fire during application and mitigate the environmental and health impact. True oils are an alternative to solvent-based lacquers and varnish, as they are 100% solids with no solvents and come from renewable resources. Shellac is also a safe finish to apply because its solvent is ethyl alcohol, which is distilled from corn. It isn’t particularly toxic nor are its fumes unpleasant.

Ingestion of finishes used for food preparation surfaces or for infant furniture used to be a serious concern before lead was banned from paint in the 1970s. However, these days, consumer-brand clear finishes are nontoxic when fully cured. All the same, when a finish is to be used for toys or in other cases where it may be ingested, it’s wise to consult the finish supplier or manufacturer. The only totally safe edible finishes I’m aware of are food-grade wax, pure natural oils, mineral oil, and shellac.

If your finishing environment is cold or dusty, fast-drying evaporative finishes and spray-applied reactive finishes like catalyzed lacquer are engineered to dry dust-free in minutes. Evaporative finishes like shellac and lacquer are the least temperamental in cold temperatures and can be easily modified by adding retarder in hot and humid conditions.

Resins, Solvents, and Additives

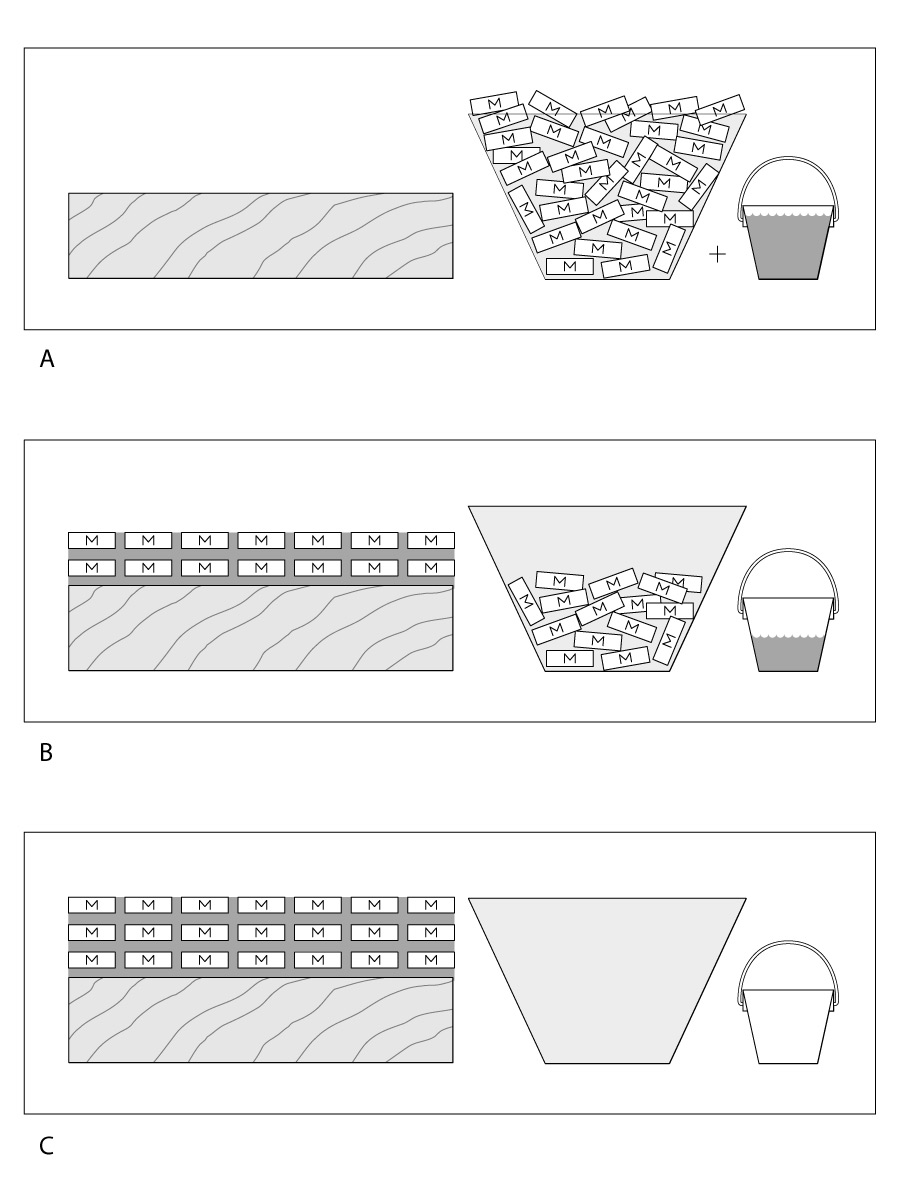

Most clear finishes consist of a resin, solvent, and additives. The resin provides the finish’s protective and decorative qualities. Solvents adjust the viscosity so the resin can penetrate and adhere to the wood. Solvents also help control flow-out and leveling and make application with various tools possible. Additives adjust viscosity and determine the satin or matte appearance of a finish. Some additives promote curing or extend the life of the finish—both in the can and after it’s applied.

Resins

Rather than choosing a finish based solely on whether it’s a varnish or lacquer or some other marketing mumbo-jumbo, it’s better to pick it by resin. Below are current resins used in wood-finishing products, although a finish may contain several resin types.

Acrylic resins feature good adhesion, hardness, light stability (most don’t yellow), and good rubbing qualities. These resins can be reactive or evaporative.

Alkyd resins offer toughness, adhesion, and flexibility. Alkyds wind up in many finishing products including varnishes, lacquers, conversion finishes, and water-based finishes.

Amino resins are extremely tough but too brittle to be used alone, so they’re combined with alkyds and other resins to make conversion lacquers and varnishes.

Shellac has excellent adhesion and rubbing qualities, although it can be damaged by heat and doesn’t offer great solvent resistance.

Phenolic resin is a hard, brittle compound that is typically combined with tung oil to make varnishes. It has very good exterior durability and is the base for many exterior varnishes.

Urethane is a tough synthetic resin that provides excellent resistance to solvents, heat, and abrasion. There are two distinctly different versions. One is prone to yellowing and suited only to interior applications. The other is a nonyellowing, exterior-rated urethane.

Cellulose is a synthetic resin made from the cellulose in cotton or wood. There are two types used in finishing products: nitrocellulose and cellulose acetate-butyrate (CAB). Both are brittle, hard, and fast-drying. Nitrocellulose is prone to yellowing, while CAB lacquers yellow less.

Vinyl is a general term used to describe a wide class of resins used as sealers or as resins in latex paint and some conversion varnishes. They provide excellent adhesion and flexibility. When used in top-coat finishes, they’re combined with other resins.

Linseed and tung oil are the two main drying oils used in finishing. These oils form the backbone of many other finishing materials like stains, sealers, and finishes.

Polyester comes in two- or three-component finishes that are mixed before application. This resin creates a very hard, tough finish that can be built up thickly without cracking or checking.

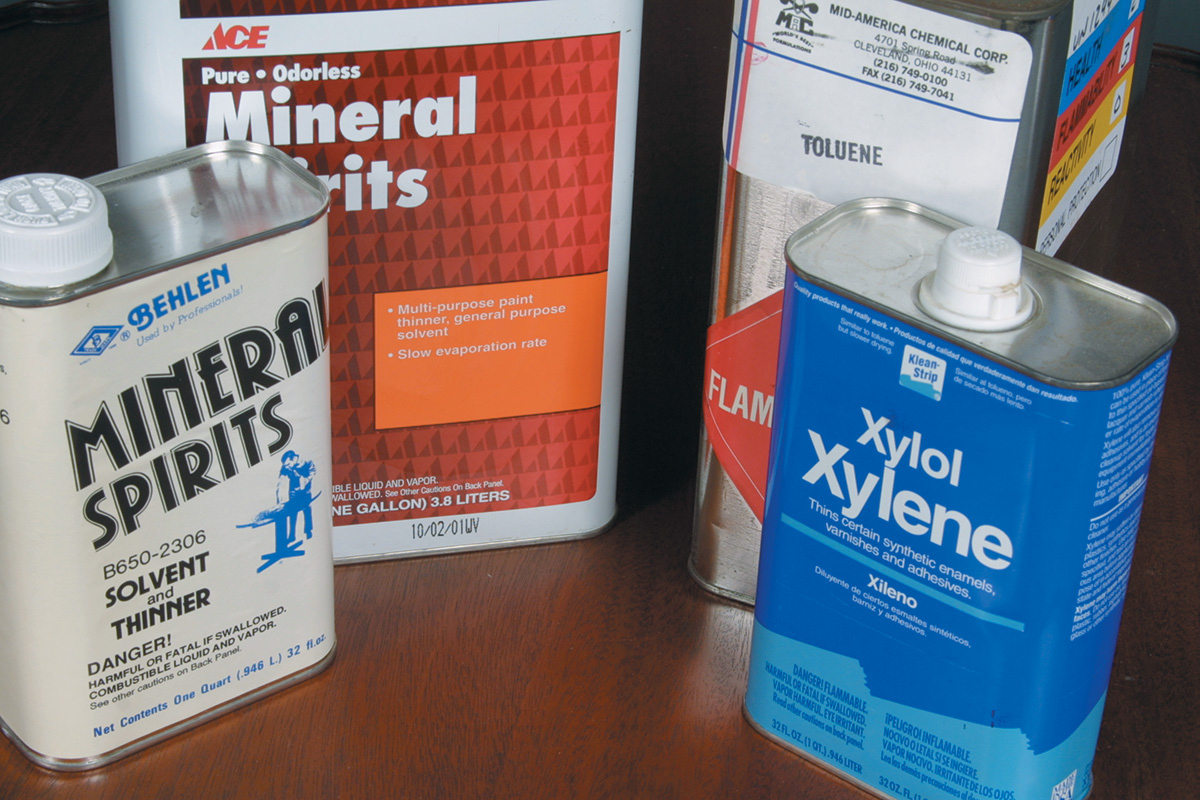

Tip: There’s some confusion between the terms “solvent” and “thinner.” A solvent is a liquid that dissolves or breaks up the resin in a finish, reducing it to a liquid state, while a thinner is simply a compatible diluent liquid that reduces the viscosity of paint or varnish but is not a solvent for the resin.

Solvents and Thinners

The types of solvents that are used in finishes and finishing products can be divided into groups or “families” that share common chemical characteristics. It’s important to have at least a basic working knowledge of how different solvents interact with the resins in finishes.

Water dissolves dyes and many resins (such as gum arabic), but these aren’t used as finishes because they’re water-soluble. Water is used only as a thinner, and any finish can be commercially formulated as water-thinnable.

Hydrocarbons such as kerosene, mineral spirits, naphtha, paint thinner, toluene, and xylene serve as both solvents and thinners. They are separated into two classes: aliphatic and aromatic. Aliphatic is slower-evaporating and oilier, while aromatics evaporate faster.

Terpenes (turpentine and d-limonene) are derived from plants: turpentine from pine trees and d-limonene from citrus trees. These solvents are almost 100 percent interchangeable with the hydrocarbons listed above and are preferred by those who have adverse reactions (mostly odor-related) to petroleum-based hydrocarbons.

Denatured and methanol alcohol dissolve most natural plant and animal resins, like shellac, as well as some synthetic resins. They also dissolve dyes. They’re widely used in conjunction with other solvents for thinning synthetic finishes like lacquer.

Ketones like acetone and methyl ethyl ketone are solvents for lacquer resins and some conversion finishes, like catalyzed lacquer and polyester.

Glycol ethers are unique in that they will dissolve many natural and synthetic resins and readily mix with water. Their wide compatibility with many solvents and resins allows formulations of water-based finishes. They evaporate slowly and are used as retarder for fast-drying finishes.

Additives

Manufacturers use a variety of additives in finishes to suit a whole range of purposes. Some make a finish more viscous; some accelerate the curing; others make it less glossy or prevent the finish from forming a skin in the can. Some improve flow-out and leveling and some prevent bacteria and mold. Although you have no control over what the manufacturer puts in the can, there are a few common additives available to finishers to help solve particular problems.

Retarders are used to slow down the evaporation of certain solvents to prevent problems like blushing or poor flow-out and leveling. Common retarders include glycol ethers, as well as slow-evaporating ketones, hydrocarbons, and alcohols.

Japan drier will accelerate the cure of oil-based finishes in cold weather.

Ultraviolet light stabilizers are divided into two classes: ultraviolet light absorbers (UVAs) and hindered amine light stabilizers (HALs). The former protect stained or bare wood from fading or changing color, while HALs protect resins from deteriorating from UV exposure.

Flow-out additives solve the problem of “fisheye” and other incompatibility issues between the finish and the wood surface, often caused by silicone contamination.

Flatting agents are used to decrease the sheen of a finish. Although you can add these to a finish, it’s best to simply purchase finish that’s already formulated for your desired sheen, such as flat, semigloss, or satin.

Tip: Paint is simply a clear finish that includes enough pigment to hide the wood’s grain. Because white is the most opaque and fade resistant of all the pigments, most consumer paints include it.

Testing a Finish

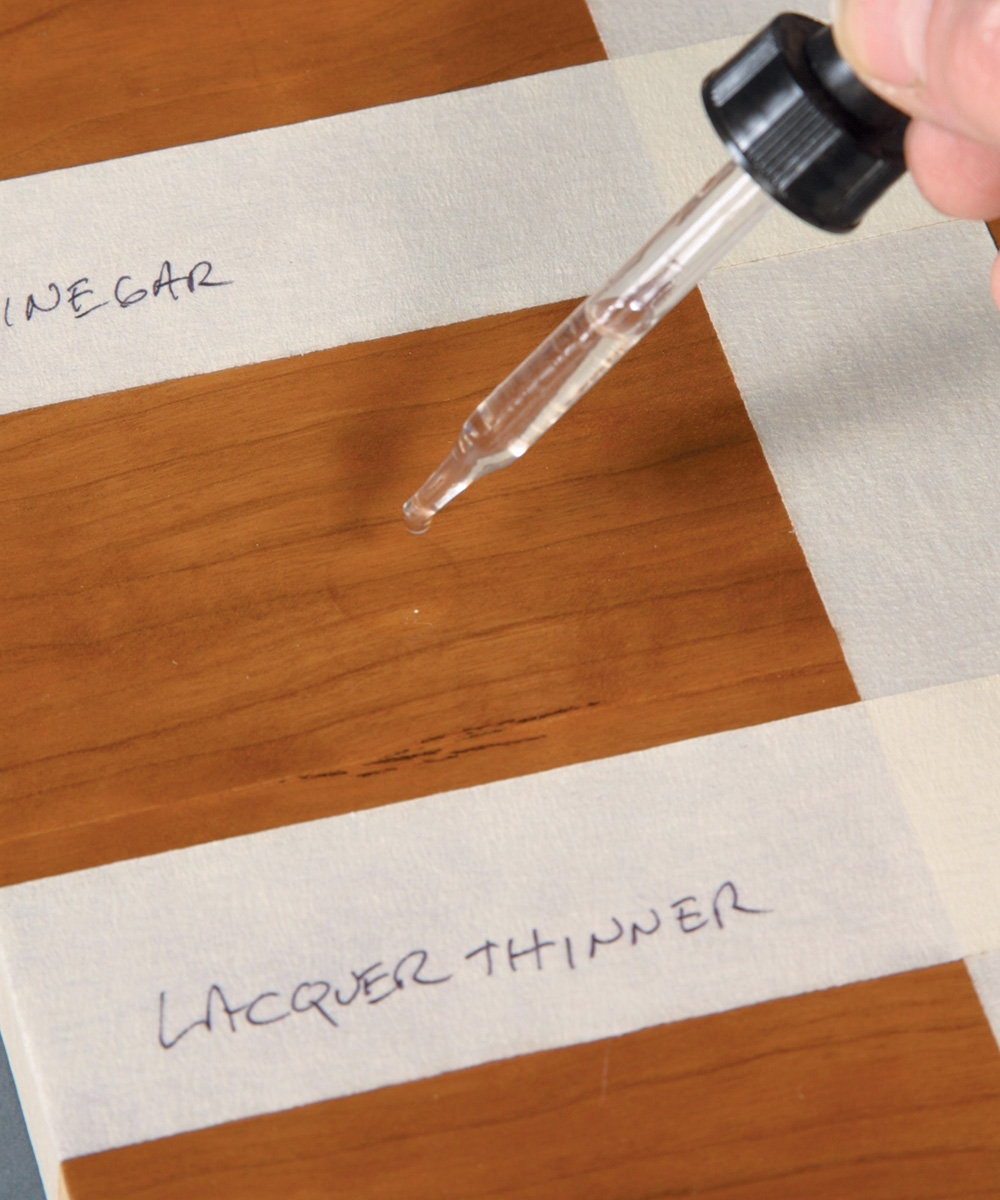

If you’re unsure of the particular qualities of your chosen finish, it’s always wise to test it on scrap. The three primary issues of concern are adhesion, hardness, and water- and solvent resistance.

When you’re applying a finish over stains, glazes, or other finishes, good adhesion is important. If you’re unsure as to the compatibility of the various products, you can perform a simple adhesion test.

To test the hardness of a finish, wait until it has cured, then try to make an indentation in it using your thumbnail. Alternatively, use a ballpoint pen to write on a piece of paper placed over the finish, then check for writing impressions in the finish.

To check the fully cured finish for water and solvent resistance, place 10 drops of water, alcohol, household cleaner, or other solvents on the surface, then cover the drops with a small dish. Wait several hours, then wipe off the solvents and check for damage.

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Odie's Oil

Osmo Polyx-Oil

Bahco 6-Inch Card Scraper

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in