Synopsis: Oily tropical woods such as cocobolo, bubinga, teak, and others pose problems when using oil-based finish. Jeff Jewitt’s solution is simple but effective. First, understand why these woods are so challenging when it comes to using oil-based finish. Then, seal off the problem with a coating of finish that isn’t affected by the oils in the wood.

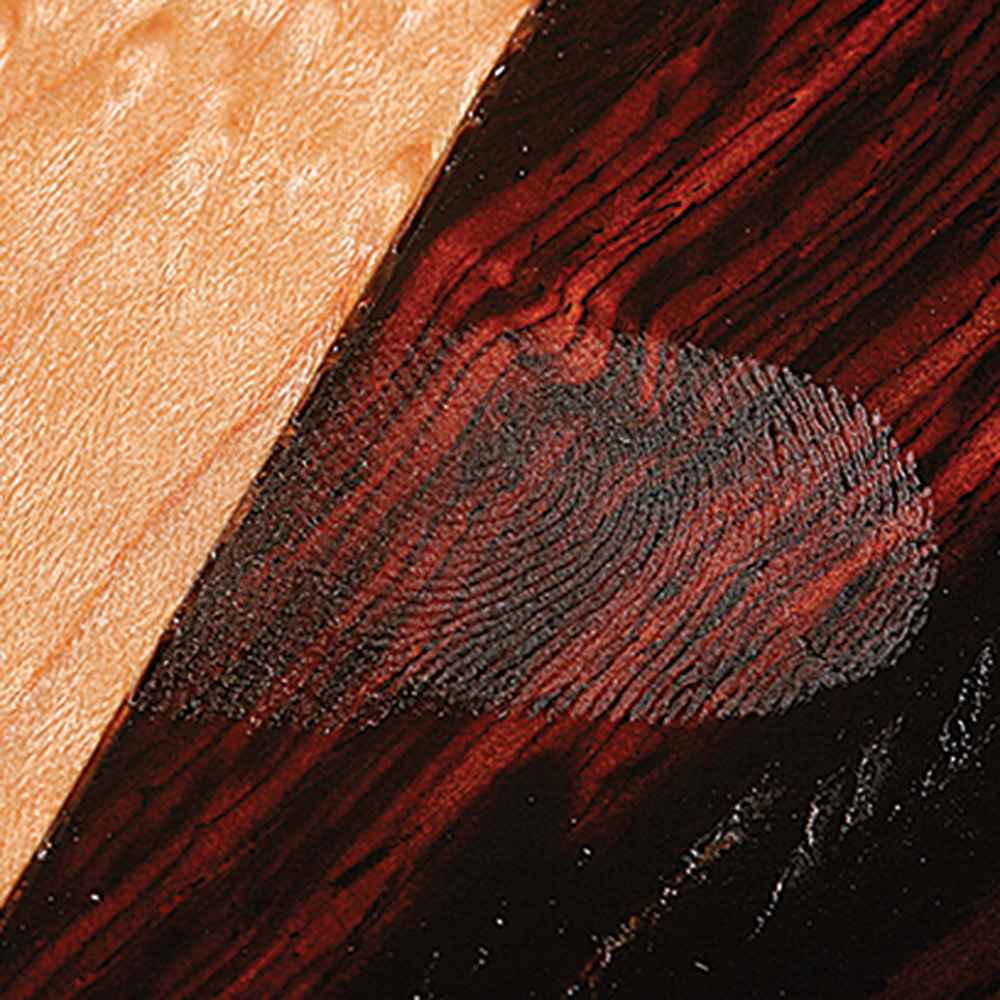

Many woodworkers use exotic tropical woods such as rosewood, cocobolo, jatoba, bubinga, wenge, teak, and others. If you’ve ever applied an oil-based finish to one of these woods, you have probably run into problems: Either the finish took a very long time to dry, dried only partially and stayed tacky, or wouldn’t dry at all. And even if the finish dried, it might have peeled or flaked off later. Your first reaction probably was to blame the finish or yourself, without realizing that the wood was in fact the culprit.

Natural oils protect tropical wood

Tropical and rain-forest woods have developed a natural resistance to the accelerated decay caused by their hot and steamy environments. Extractives (commonly referred to as oils) produced by the trees are naturally water repellent and rich in chemicals known as antioxidants. These impede or slow down the oxidation of other molecules, which is the first step in the decay process.

To understand why these wood oils affect oil finishes, you have to understand how oil finishes cure. Drying oils like soya, tung, and linseed (and the varnishes and polyurethanes based on them) begin to dry by absorbing oxygen from the air into the liquid finish on the wood’s surface. The oxygen combines with molecular components of the finish, forming other chemical molecules, one of which is a free radical. A free radical is like a molecule on steroids. It has too many electrons, making it highly reactive (chemists call this unstable). The free radical accelerates the final stage, which is polymerization (curing) of the finish.

On tropical woods, this process is impeded by the antioxidants in the oily wood. Antioxidants donate a portion of their electrons to stabilize the free radical, thus neutralizing it. As a result, the final curing or hardening of the oil-based finish is slowed down dramatically.

Shellac is the answer

When I was learning to finish, I was told to wipe down oily woods with lacquer thinner or acetone prior to applying oilbased stain or finish. This helps with the adhesion issue (finishes don’t bond well to oily woods) as long as you apply a finish within minutes, but it may not help with the curing problem. This is because the evaporation of the solvent pulls more oil to the surface of the wood.

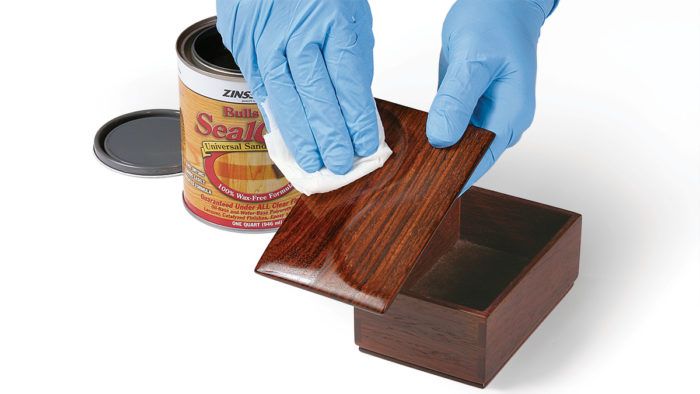

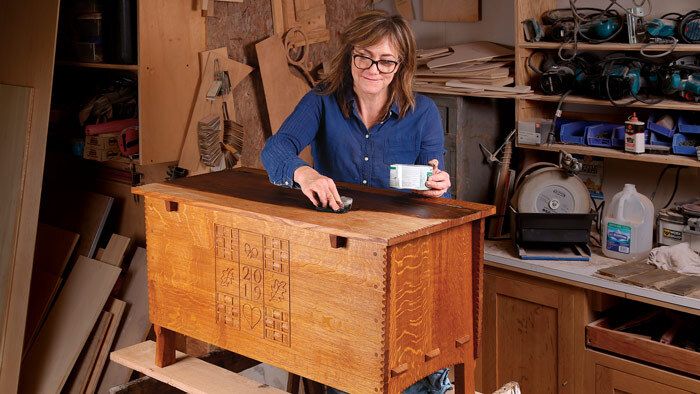

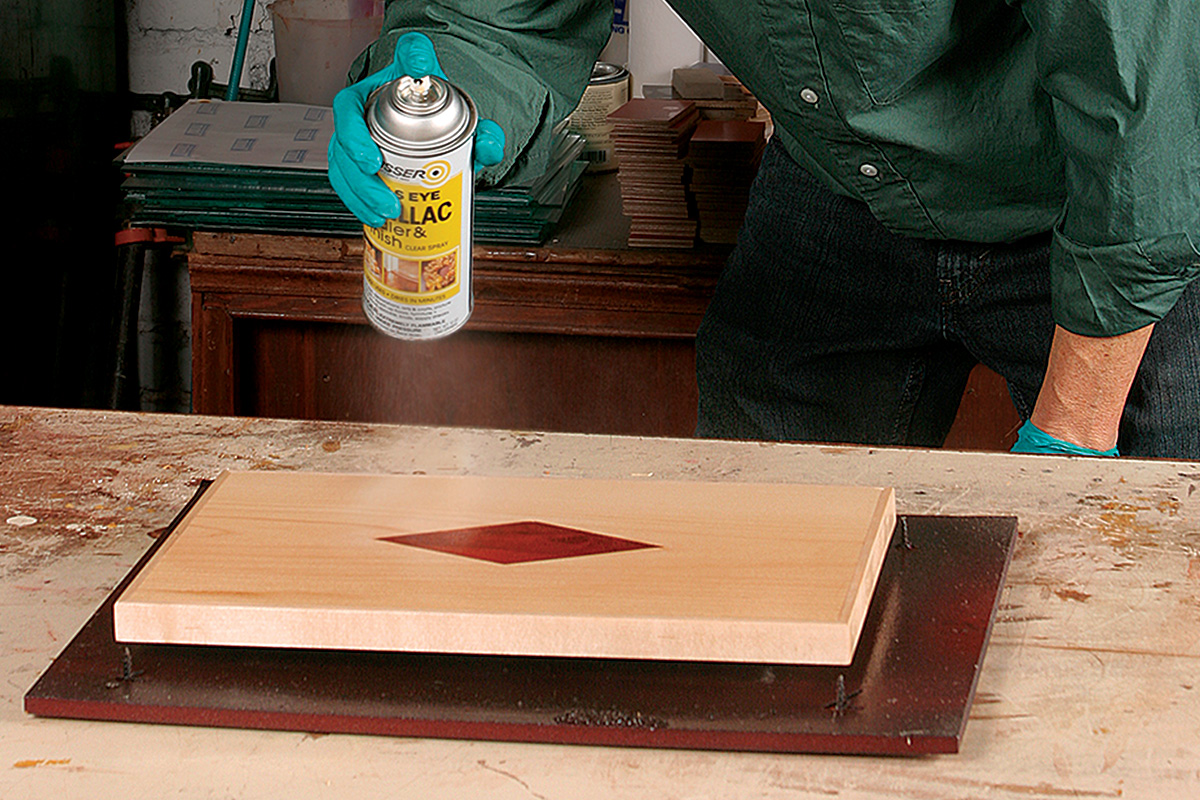

A better strategy is to seal the wood with a thin barrier of a finish that isn’t affected by the oils. For solvent lacquer, you can spray on a barrier of vinyl sealer, but for most finishes, use a coat of dewaxed shellac. You should use either readymade, wax-free Zinsser SealCoat or make the shellac from dewaxed flakes.

From Fine Woodworking #203

To view the entire article, please click the View PDF button below.

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Waterlox Original

Odie's Oil

Foam Brushes

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in