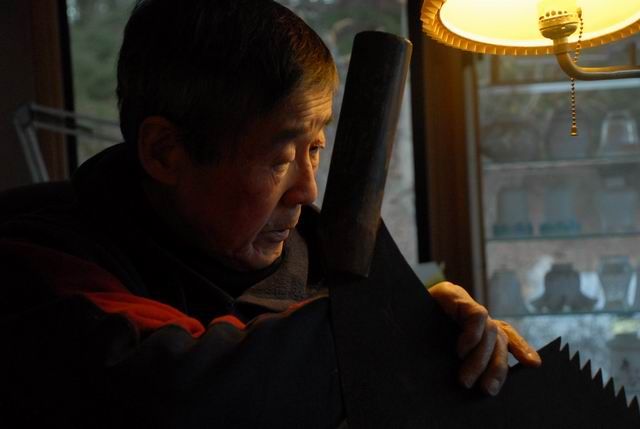

Master craftsman and teacher Toshio Odate examines the author's maebiki-oga.

I didn’t intend to visit Toshio Odate for an official interview as an associate editor at Fine Woodworking. My wish to visit him came out of the desire to find out more about two tools I had in my shop—a large log-ripping saw called a maebiki-oga, and a side-trimming plane I had recently picked up on eBay.

Of course, I can’t hide that was more than excited to meet an author I had admired for many years, ever since I picked up a copy of his well-known “Japanese Woodworking Tools: Their tradition, Spirit, and Use.” When I mentioned Odate to the manager of a local woodworking club, he said “you’d be foolish not to visit him—he’s only 20 minutes away from you!” And so I called up Mr. Odate and made an appointment.

A few days later, I was pulling up his driveway on a late Connecticut afternoon. As I parked and got out, Odate came out to his back porch to meet me. I didn’t bring out my wooden Japanese toolbox or the big saw just yet—I worried I’d drop the box or the saw on somebody, and even though I’m well-versed in making a fool of myself, I decided against it for the time being.

|

More on Japanese Tool Tech

|

After taking off my shoes at the entrance, Odate welcomed me to his sitting room, where an amazing collection of vintage power line insulators adorns the walls, along with other funky glassware. I met his assistant, Laure Olender, who takes photographs of all of Toshio’s work. I sat down and made only the smallest of small talk—which was not necessary. I sensed in a few moments that there is no need to be anything but full-on with Toshio Odate—and that it pays to listen.

I asked about the large ripsaw, or maebiki-oga, and Odate asked me to bring it in to show him. After a few minutes looking at it, he explained to me what I was wondering about: the maebiki of that size have specially-shaped teeth, usually on the front third or half of the blade. These special teeth give purchase so the blade can dig in better as it approaches the end of its glide, where the power of the user’s pull plus the blade’s own inertia is least. Other Japanese saws, like the more commonly-known ryoba or dozuki, have the tooth line at an angle compared to the blade’s back (or centerline, for the ryoba). This angle digs in more as the user reaches the end of the blade’s length. Odate mentioned that in woodworker’s slang, these teeth were sometimes called chon-gake. It was gratifying to learn this small, if somewhat esoteric, detail about my saw.

Toshio added that this kind of information is not what most woodworkers are interested in, and it is indeed esoteric—but he’d still include it if he were to write a book dedicated to the art and life of the kobiki, or sawyer. And here is where Toshio added something very important: there is something else that is not always being grasped by many woodworkers in the craft: the social responsibility of the craftsperson, be they woodworkers, musicians, photographers, doctors, or writers. Each of these persons practices a craft and in that craft they are expected to produce a result that carries with it a social responsibility. And that responsibility is where the person’s skill and even artistry must be used to serve others. For example, if a joint is used to show off a person’s ability to create a showy piece, but fails when it comes to joining two pieces of wood securely and efficiently, that person has failed at their responsibility to society—even if the joint “looks beautiful.” But the craftsperson who makes a solid joint, that looks “good enough,” does its job and holds for decades or centuries to come—that person has fulfilled the responsibility society asks of them. Even if that joint is hidden, it has the spirit of being a good joint. Odate made a comparison to comfortable and attractive undergarments—they are out of sight, but if they are strong, comfortable, warm, and last, they’ve done their job well, and can even bring a smile to the wearer’s face (I’ll admit that the comparison brought smiles to our faces at the time).

What about hobbyist and enthusiast woodworkers, I asked? If you are a hobbyist or enthusiast, Odate explained, and you are not publicly committing yourself to being a craftsperson for public hire, you don’t have the weight of that social responsibility. But once you commit to making a piece for a client, or a family member, that responsibility is there, to those people. It’s your job to make sure your design and your workmanship serve the needs and desires of your clients, and that the techniques and materials you use serve those ends. Anything else is superfluous, and runs the risk of being dangerous, or at best, ugly.

Wise words, from someone whose experience of over three quarters of a century has spanned an apprenticeship as a tategu-shi (sliding screen door maker), a woodworker, a teacher, and a sculptor. Odate has fulfilled responsibilities in all of these areas, and shows no sign of planning to diminish his creative output.

Toward the end of the evening, Odate shared a wonderful insight. Indicating the rich, warm patina of a tremendous plank table in his kitchen, he mentioned the idea of the “user’s finish”—the fact that no piece is really complete until, 50, 100, or 300 years down the road, the thousands of users’ hands handling a piece have given it the true finish, one that the maker could not give when the piece was assembled. It speaks of the present-day craftsman imbuing his or her work with their intention and sense of social responsibility, and projecting that skill and care towards the future, where further generations will be able to feel the woodworker’s spirit with them still.

Comments

can such a spirit survive in a materialistic , competitive, free enterprise society .perhaps we need to change society . the present approach isn't doing too well .

Is that table from the white oak plank that we heard about a few years ago? It would be great to profile it again and see how the users' finish is developing. It's always an insipration to hear from of one of the living masters of woodwork.

I think the spirit is very much alive today in the right person. I don't sell my work but a friend asked me several years ago to make him a work bench for working and dying his leather for his business. I could have just glued as screwed it together to be good enough. Instead, I used mortise and tennon joinery in the craftman style. It does not look pretty but after years of tough use to this day it does not shift, move or wiggle while work is being performed on it. I have so little time to do the wood working I enjoy that when I do get the time to do it, whatever I make I want it to last.

ipower, you are so correct. The persent is not doing very well. The craftsmen of the past are dwindling to a select few. The young today do not want to take the time to design and create masterpieces. The are contented with just GOOD ENOUGH, not MAGNIFICENT. The masters are waning and there is nobody willing to make the committment to apprentice under them.

Unfortunately, I was brought up durring the begining of the 'instant' age, my father wasn't a woodworker and I had no exposure to it, other than 'shop class' in school, until later in life. Now I am trying to catch up but it is really too late. We need to challenge our young people, we need to intice them into being more creative, we need to instill patience and vision in their souls.

Hopefully we will continue to find a select few to take up the banner and continue learning, and teaching, the time honored practices of the Masters so that tradition isn't lost in the 'instant' society we've become.

Although the hobbyist woodworker does not necessarily have the social responsibility, they should still have a responsibility to self. If they are not putting their best effort into the task, then they are compromising their integrity for the sake of expediency or mediocrity.

Even if the results are not perfect, if it is the craftsman's best effort, then they have done their duty to self. They can do no better. They can increase their skill and achieve better results, but the effort is an honest one, not one of compromise.

That same issue is reflected in a significant portion of society where "doing your best" or "doing the right thing" gets whittled down in the name of competitiveness or profit.

Some years ago, I had the pleasure of taking a course with Mr Odate on Shoji making at the Brookfield Crafts Center in CT. Besides learning some basic skills from an amazing craftsman, I had the privilege of spending some hours with a very warm and generous human being. It was an honor to study with him.

Barry

Thank you for a very interesting article. True to the discussion it felt more spiritual than instructional.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in